Wabash Station, A Massacre, and Columbia’s First Railroad

On January 30, 1857 the Boone County & Jefferson City Railroad Company was incorporated in the state of Missouri. The company’s goal was to construct a railroad from the proposed North Missouri Railroad in northern Boone County through Columbia to the Pacific Railroad in Jefferson City. After being put on hold during the Civil War, the line was completed in 1867. Although the line from Columbia to Jefferson City was never constructed, the railroad from Centralia to Columbia was the city’s first rail connection. In 2023, it is known as the COLT Railroad and is Columbia’s only active railroad. The track is now owned by the City of Columbia and operated by City of Columbia Utilities. The 1909 Wabash Railroad Station and Freight House on 10th Street in Downtown Columbia was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

The Boone County & Jefferson City Railroad was largely the result of the efforts of one man: James Sidney Rollins, father of the University of Missouri. In 1836, at age 24, Rollins traveled to St. Louis to attend the first railroad convention in Missouri, as a representative of Boone County. He began three decades of advocacy for rail transport to come to Mid-Missouri. It took fifteen years, until 1851, for real plans to materialize when the North Missouri Railroad was granted a charter to build a railroad from St. Charles, Missouri to the Iowa state line. The exact path was up for debate. The original plans called for the mainline to pass through the city of Columbia then turn north toward Iowa. Opposition from slave owners in Callaway County forced the route north to Audrain County. The Callawegians were Jeffersonian agriculturalists suspicious of industry, who feared the creation of an escape path for enslaved people.

Possible Routes Of The North Missouri Railroad

Created by Marty Paten for his book The Columbia Branch Railroad: A Chronological History of the Short Line Railroad from Centralia, Missouri to Columbia, Missouri

The chosen route did pass through extreme north Boone County and the cites of Centralia (1857) and Sturgeon (1856) were founded as stations along the new North Missouri Railroad. Four men: James S. Rollins, David H. Hickman, R.L. Todd, and William Switzler immediatly responded by incorporating the Boone County and Jefferson City Railroad Company to connect Columbia to the mainline in either Sturgeon or Centralia. The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 stopped all progress. The North Missouri Railroad, controlled by the Union Army, was the focus of attack by confederate guerilla warfare and sympathizers. In an attempt to stop Union troop movement the track was torn up or blocked multiple times by bushwackers. During the summer of 1861, the now infamous William Quantrill and “Bloody” Bill Anderson attacked the railroad, burning depots and bridges, tearing up track, and tearing down telegraph lines. Sometimes they stole trains. It was three years later, in 1864, that the most infamous event of the civil war in Mid-Missouri occurred: The Centralia Massacre.

The Centralia Massacre took place on September 27, 1864. The night before, nearly 400 confederate bushwackers had camped along Young’s Creek, southeast of Centralia after failed attacks in Fayette and Glasgow. The men woke up tired and often drunk the next morning. At 10:00 a.m. Bloody Bill Anderson led about 100 men into Centralia to find a newspaper that reported news of the war. Centralia was a small town, less than a decade old, and activity was centered at the North Missouri Railroad Depot. As the men entered town they began to loot stores and force themselves into homes, demanding breakfast. Some went straight to the railroad depot where they discovered shipments of boots and a whiskey barrel. Drunkenly, they began to destroy everything in sight, running horses through town, cursing and violently attacking the citizens.

During the chaos the stage coach from Columbia arrived, carrying none other than James S. Rollins in it. Despite being a slave owner, Rollins was a staunch Unionist and a U.S. Congressman who was a key ally of Abraham Lincoln. Knowing that the bushwackers would quickly murder him if they recognized Rollins, he identified himself as “the Reverend Mr. Johnson minister of the Methodist Church South,” emphasizing the word “South”. They began to search him and would have found paperwork identifying him as the famous Unionist James S. Rollins, but were distracted as the westbound train of the North Missouri Railroad arrived in Centralia. So began the massacre, as the train stopped the locomotive and passenger cars were bombarded with bullets. The cars were full of men, women, children, and unarmed Union soldiers. The guerrillas ordered the civilians off and robbed everyone. The union soldiers were ordered to strip naked, line up along the track, and Bloody Bill ordered the massacre of at least 23 unarmed union soldiers; The train tracks were covered in blood. The locomotive was set on fire and sent unmanned down the line to Sturgeon. The bushwackers regathered and escaped town, back to camp. The battle of Centralia would unfold that afternoon a few miles southeast of town, after the Union arrived in Centralia and discovered the carnage.

Once the Civil War ended, and the mainline of the North Missouri Railroad repaired, Rollins would again lead the charge to construct a branch into Columbia. A meeting was held on October 5, 1865. The Missouri Governor, University of Missouri President, and church clergy all supported the effort. James L. Stephens was elected president of the Boone County and Jefferson City Railroad Company. David H. Hickman assumed the role later that year, and in 1866 a petition was signed by 1,500 people supporting the effort. Construction started in 1866 and was completed in 1867 to grand celebration. The first Columbia depot building was likely timber and wood. Almost forty years later, in 1907, a limestone depot was constructed. By this point the track was owned by the Wabash Railroad, and the station would be called Wabash Depot. The building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, and is now a fixture of Columbia’s North Village Arts District. In 2023, it is Columbia’s main bus stop and home to Columbia’s Public Transit offices. The train no longer travels south of Business Loop, but its railroad history is depicted in an outside sculpture and inside oil paintings by local artist David Spear.

A Postcard of Wabash Depot In The Early 1900s

From COMO Magazine’s Discovering the History of Trains in Columbia

Wabash Depot in July 2009

From Wikimedia Commons taken by HornColumbia

The National Register of Historic Places nomination form, prepared in 1979 by Linda Harper, describes the Wabash Station and Freight Depot as follows:

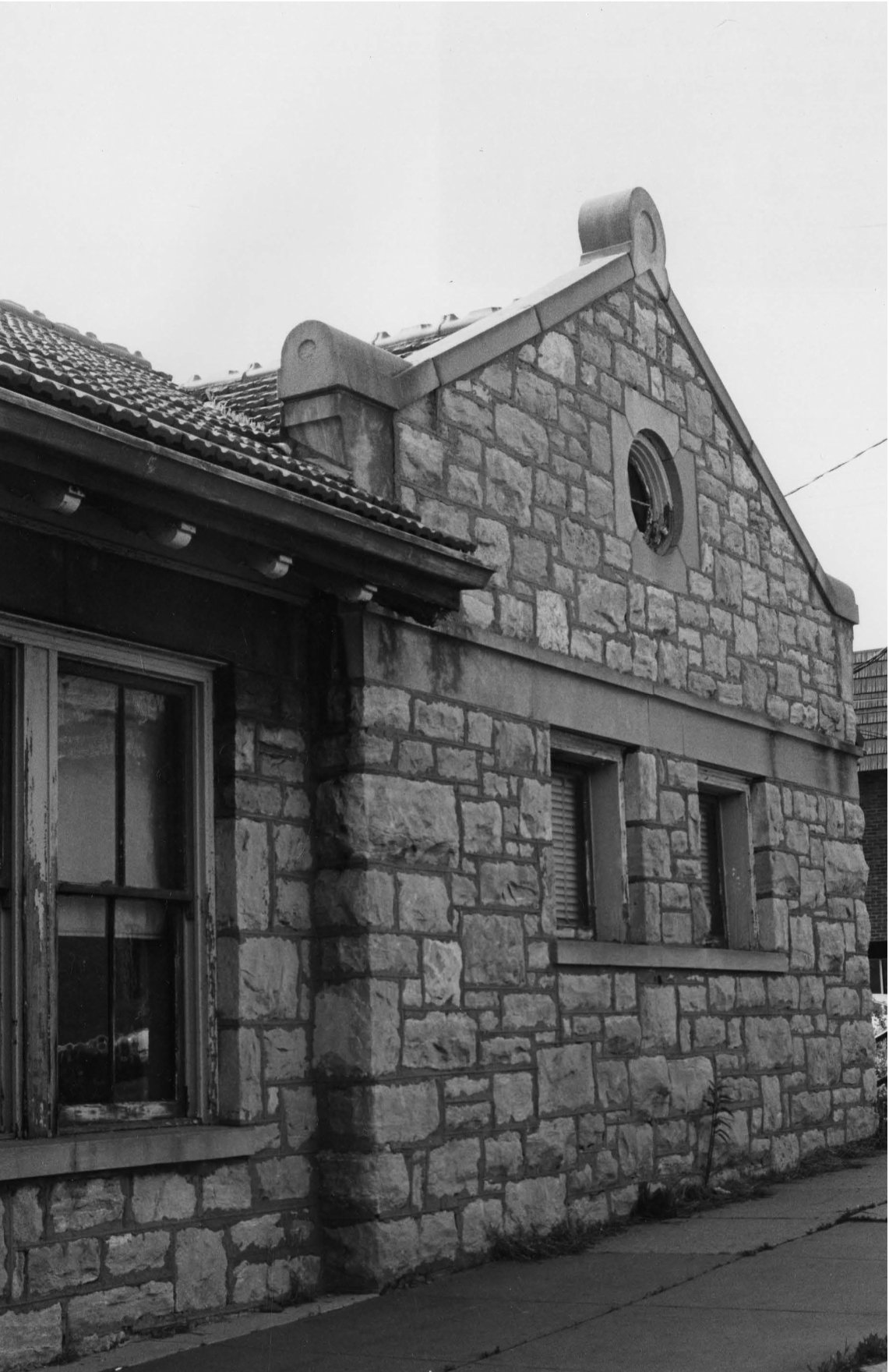

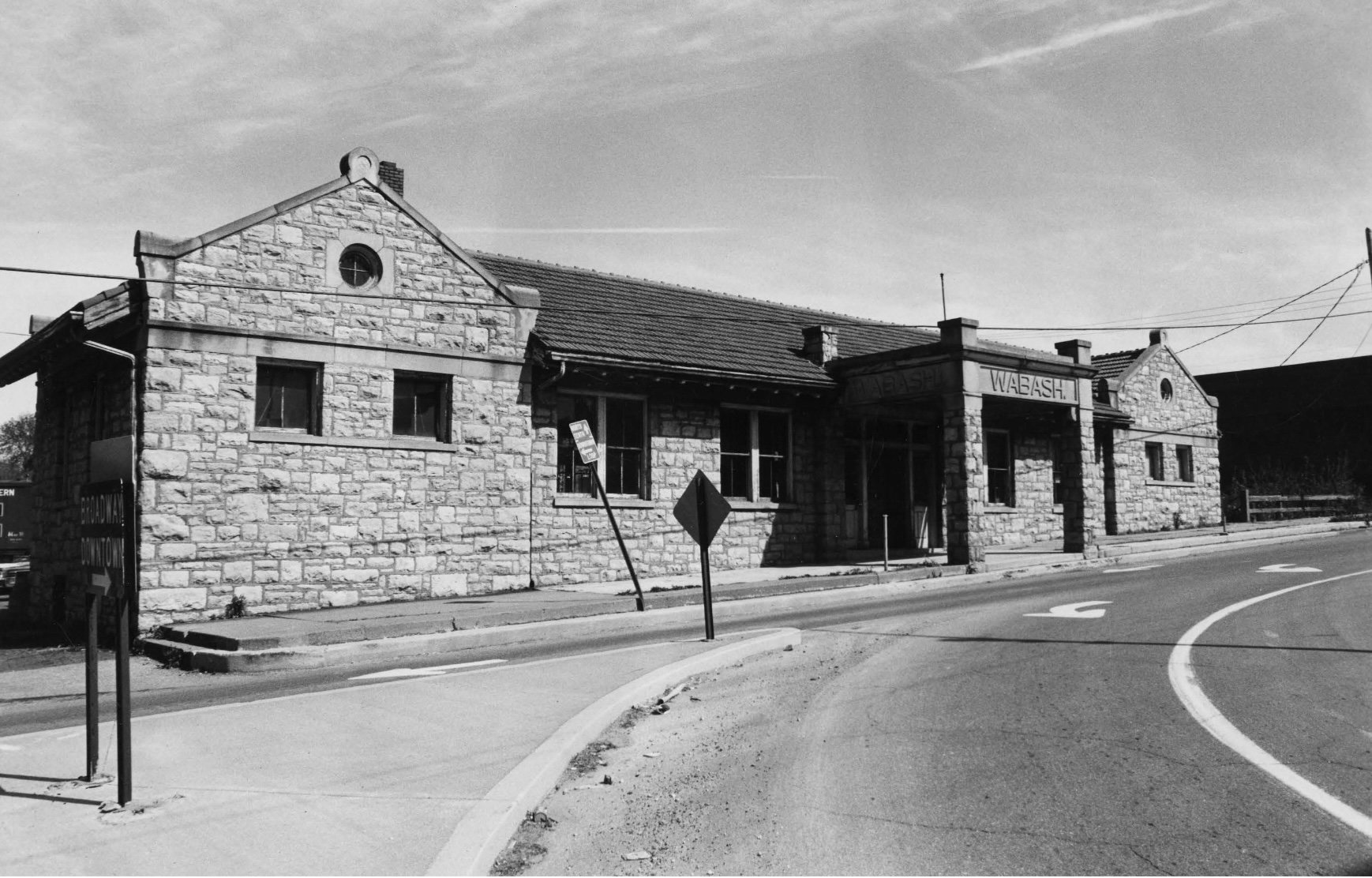

“The Wabash Station is a one story, H plan, Jacobean style building. Built of rock-faced ashlar cut stone quarried locally, it sits on a stone and concrete foundation with a partial basement under the north end. Referred to in 1909 as a Tudor-Gothic design, the exterior has several important features, such as a 3 part gable roof with grooved, interlocking red clay tiles and its distinctive stone copings along the parapet walls, the two entrance porches, and the small circular, attic story windows of Tudor quality in the front and back of each gable end.

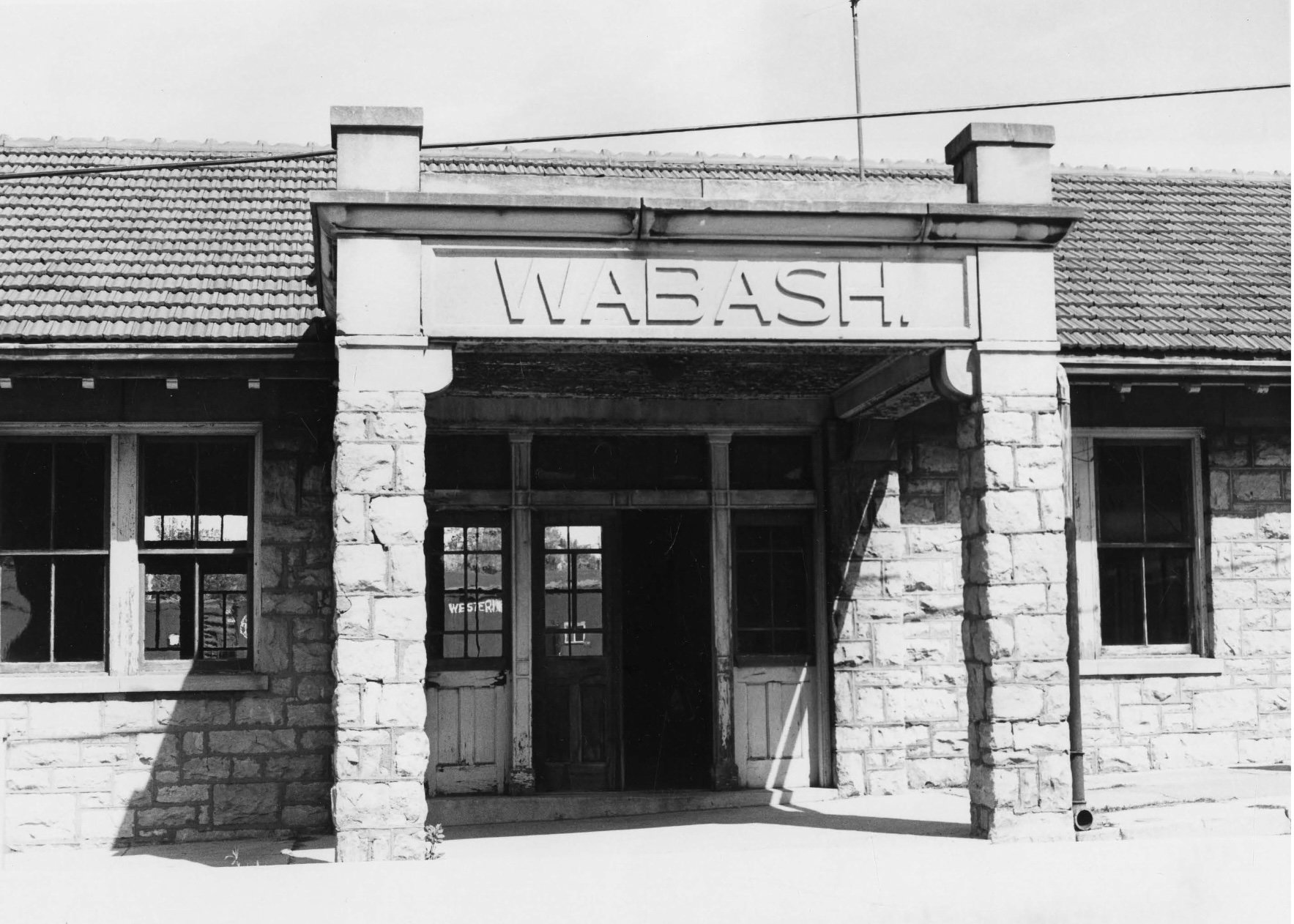

The station can be entered on both the east and west sides through large double doors with transoms. The west entrance has a 131 x 15' portico which extends to the curb and served as added protection for those people arriving in hacks. On all three sides of the portico one can read. "WABASH" carved in stone. Since the tracks are lower than, the street and the floor of the building is harmonious with the the street entrance and level, the east entrance porch in front of the two double doors and the center projecting bay is designed, as a wide uncovered concrete, U shaped, terrace with four steps leading down to the tracks.

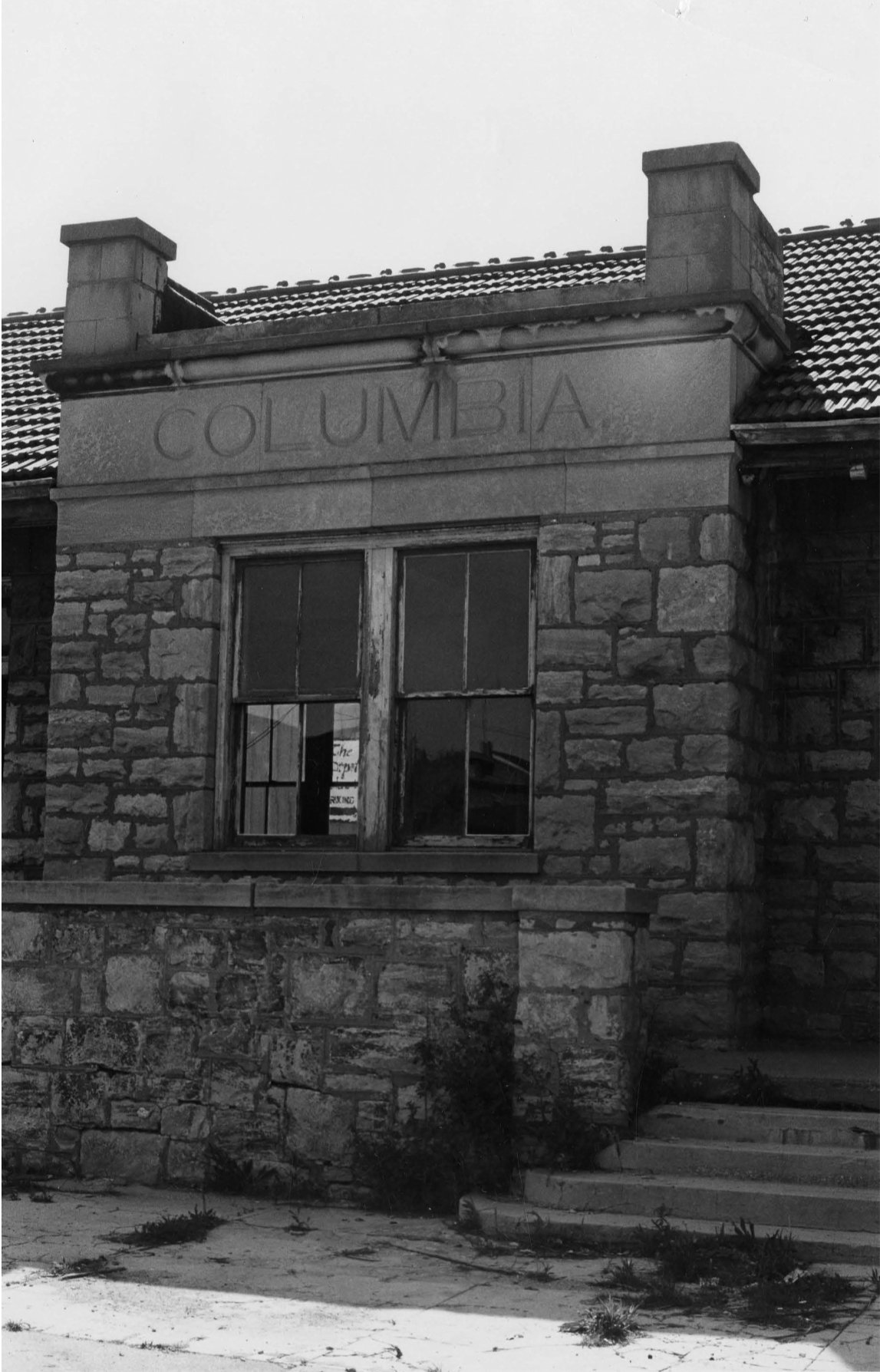

On the projecting bay is the word "Columbia", with the 18" letters carved in stone. Details of decorative stone work, roof tiles, and the brackets at the eaves can be seen in Photo 5. Built to serve only as a passenger station, the interior construction and design lent itself to a more "home-like" atmosphere and was finished in mahogany woodwork with the ticket offices, with ticket windows still intact, are at the south end; the ladies waiting room, 18' × 17', and the restrooms are at the north end; and 'the large, 52' x 21', general waiting room with its 3' × 11' projecting bay is in the center.

In the main room the ceiling is plastered. Four beams are exposed exemplifying King Post trussing with auxiliary braces. Interior walls are plastered and painted. Costing approximately $15,000 and measuring 106' × 27', the building was constructed by Leonard Wolfe, St. Louis, and contains all the modern conveniences. It was heated by hot water; the heating plant and fuel storage tanks located in the partial basement.

Unlike most stations, there is no platform covering or extended eaves. A concrete platform was laid at the same time as the station was built. It was intentionally large and long as exemplified by this statement: "the platform will run along the east side and the north end of the building, allowing ample room for crowds.”

Many improvements were made to the yards and tracks at this same time. Because of the new station's location and that of the freight house, a Y track was also implemented. This enabled the trains to back in, thus depositing passengers and freight at their appropriate destinations.

The Freight House, an important element in that it is the original depot, was built of tongue and groove frame construction and was a combination depot, serving both freight and passengers. Lying just northeast of the new station, it measures approximately 90' × 26'. By converting this structure into the freight house and not tearing it down, the Railroad was able to maintain an office with adequate service during the construction of the new station. Even though it was altered to more favorably suit its new purpose a few of the old characteristic elements still remain, such as some of the original large sliding freight doors and the extended 6' overhang of the eaves with slightly decorative brackets. The interior has concrete floors; walls and ceilings were originally covered with beveled wood siding, but much of this has been removed, leaving the framing exposed. There is electricity to the building but no heating or plumbing.

These two buildings are located in the urban setting Just a few blocks from the heart of downtown Columbia and are surrounded by a mixture of other buildings, such as churches, businesses, and a few remaining residences. To be noted is the First Christian Church, built 1892, just across 10th St. from the station. This building, also of native stone, gives a visual coherence to the area.”

Inspired by the preservation of a historic train station, our group, CoMo Preservation, hopes to help homeowners, landlords, and institutions prevent the destruction of historic architecture. Original period styles might be replicated, but will forever lack the social history of authentic structures. The preservation of historic buildings is necessary for Columbia’s residents, students, and visitors to achieve a sense of place and, it follows, for our city’s continued economic success. If you want to join us in our mission sign up for our mailing list to receive news and updates.

Sources:

Switzler, William F. (1882). History of Boone County. St. Louis, Missouri: Western Historical Company. OCLC 2881554.

Harper, Linda (June 1979). National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Wabash Railroad Station and Freight House. Columbia, Missouri: Columbia Art League. Accessed January 30, 2023.

Havig, Alan R. (1984). From southern village to Midwestern city : an illustrated history of Columbia. Woodland Hills, California: Windsor Publications. ISBN 9780897811385.

Crighton, John C. (1987). A History of Columbia and Boone County. Columbia, Missouri: Computer Color-Graphics. OCLC 16960014.

Paten, Marty (2012). The Columbia Branch Railroad: A Chronological History of the Short Line Railroad from Centralia, Missouri to Columbia, Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: HAGR Publishing. ISBN 978-0-615-52810-6.

Patston, Matt (August 19, 2016). Discovering the History of Trains in Columbia. Columbia, Missouri: COMO Magazine. Accessed January 29, 2023.

Do you have ideas for future topics? Interested in writing an entry or sharing a photo? Did you notice an error?

Email CoMoPreservation@gmail.com or leave a comment below.