Greenwood

On January 15, 1979, Greenwood, one of Columbia’s oldest surviving brick structures, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The home, is “a remarkable example of the Federal style as interpreted locally and exhibits a high degree of preservation of original features.” It was the home of Walter Raleigh Lenoir, a member of a wealthy and influential family. There is some debate over when the oldest part of Greenwood was built, but at earliest it was 1827 and at latest 1839; Columbia was founded in 1821. The house is still occupied and used as a family home today. It is very likely the oldest brick structure in Columbia.

The Federal style of architecture was the first style of architecture developed in the newly independent United States. The style was influenced heavily by the classical architecture of ancient Greece and Rome, as interpreted by Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio and American Thomas Jefferson. Monticello (built 1772) and the White House (built 1792-1800) are in the Federal style. Influential early Americans consciously chose to associate the first modern democracy with the ancient democracies of Greece and the republican values of Rome. Jefferson wanted a new architectural style for a new nation. The original Academic Hall (1840) on the University of Missouri campus was one of Missouri’s most impressive Federal style buildings before it was destroyed by fire in 1892. The federal style is only very rarely found west of Missouri.

Walter Raleigh Lenoir, born in 1787, was the son of an American Revolutionary War General. He accumulated a fairly large plantation in North Carolina, but in 1833 he sent his young nephew, William A. Lenoir, in search of a new area to settle in the twelve year old state of Missouri. His wealth and social status are demonstrated by his ownership of twenty-three enslaved people in North Carolina, who along with his family, would accompany him to Missouri. Enslaved people participated in the construction of Greenwood. Lenoir gave $100, a large donation for the time, to establish the University of Missouri in 1839.

Greenwood’s original front entrance, note the over 200 year old white oak

Taken by Matt Fetterly on December 30, 2022

The National Register of Historic Places nomination form tells the story of the Lenoir family’s arrival in Columbia and much of what is known about the construction of Greenwood:

“After a long two-month journey, the Lenoir family arrived in Missouri in November of 1834. Camping outside of the town of Columbia, they chanced to meet a gentleman "of noble worth." Explaining to him their desire to find a home in which to spend the winter months ahead, he offered his assistance and then went on his way. Once the Lenoirs reached Columbia proper, they encountered the same gentleman, engaged in a search for property that they might lease for several months. Eventually the search proved successful, for Lenoir was able to rent land about two miles northeast of the community of Columbia. [Lenoir writes:]

“After a long and fatigueing [sic] Journey I have located myself for the present about 2 1/2 miles N. East of Columbia on a rich and fertile tract of land 320 acres (a half Section) about 40 acres of which is under cultivation with tolerable comfortable cabbins [sic] and other necessary outbuildings. I have leased the place for one year and am to give two barrels of Corn of $1.50 pr [sic] acre for the improved land. I have an excelent [sic] spring convenient and a plenty of stock water, and there are three grist mills, a saw mill and a first rate school within one mile and a half, and a meeting house within a half mile of this place...and am surrounded & in the midst of a dense population [sic] approaching the nearest to an equality & I think the most hospital [hospitable] & kind people that I ever happened amongst during life, they all own valuable lands and a few slaves, and possess good natural minds and tolerably well improved, and further they are temperate and moral..”

It appears that Lenoir's original intention was to head further west within Missouri, aiming for settlement in Saline or Lexington Counties. However, the approach of winter seems to have forced him to settle temporarily in Columbia. Letters written during this period expressed his desire to travel about Missouri and to inspect possible areas for permanent settlement.

The Lenoirs began the operation of farming soon after becoming situated on the property. What slaves were not needed for the farm chores were hired out. By winter of the following year, Lenoir seems to have made his decision to remain in Boone County. In general, his letters reflected a contentment with the area indicating that even the poorest lands in Boone County would be considered of good quality in Wilkes County, N.C. He and his family were further impressed with the kindness and character of the local citizens and pleased with the results of initial attempts to farm their land..

In May of the following year, he wrote to his brother William in Tennessee, presenting his envisioned plans for a suitable dwelling house for the property:

“...within three years I hope to be situated in a comfortable brick house on a beautiful eminance [sic] Partly surrounded by a delightful grove of sugar trees, black walnut, hickory, oak and white ash, composing about 8 acres, which has been grubed [sic] and the greater part sown [sic] down in blue grass this spring, which is intended for the benefit of stock, as well as an adition [sic] to a delightful scenery."

from this Site I can have a view of 140 acres intended for grain and a Meadow of 20 acres and the greater part of sixty acres intended for a woodland blue grass Pasture. I will also be enabled to see a traveler on a very publick [sic] road runing _sic near the spot intended to build, to be situated thus is very different from that remote poverty hill from whence I came.”

However, it was not until several years after arrival in Missouri that the Lenoirs were ready to build their new home. In a letter of June 1838, Walter discussed the imminent prospect of construction of his new home:

... I am also making some preparations for building a dwelling house next summer, and think that I can have all the materials by next spring without advancing any money. My neighbor who owns the sawmill owes me for hire of hands as much as my bill for sawing will come too [sic], the balence [sic] of materials will be furnished by the labour of my own hands. I have sold about $100 worth of grain this spring, I am still enlarging my farm and it begins to look like home.

From the available correspondence, it is evident that the family was busily engaged in farming from the point of their arrival in Missouri.

The need to produce a profitable, working farm probably kept them from considering building a home immediately. Furthermore, Lenoir had not yet received payment for his real estate in North Carolina, a fact which he stressed frequently in his letters. He was therefore hesitant in his plans for building, waiting until his neighbor was in debt to him for the hire of his slaves in order that he might receive sawn lumber for his house in return.

As Lenoir indicated in the letter above, he was counting on the labor of his hands, or slaves, in the construction of the building. It is not known to what extent the Lenoir slaves participated in the construction, but they were certainly employed in the heavy labor. In addition, they probably were involved in the making of the bricks. Later correspondence of Sarah Lenoir mentioned the possibility of hiring out slaves. Whether the slaves were involved in any of the more skilled task is unknown.

Unfortunately, the actual construction of Greenwood is not discussed in the extant Lenoir correspondence. In November of 1840, Walter wrote to his brother William that he was about to build a frame smokehouse, suggesting that the dwelling house was already completed. However, the best evidence for the construction date remains his reference to building preparations in his letter of June 15, 1838 (previously cited). The years between 1838 and 1843, important ones as far as the construction of Greenwood is concerned, are little documented. By the 15th of October, 1843, Walter Raleigh Lenoir had already died. The next available letter was written by Sarah Lenoir, in which she spoke of her late lamented husband. The heading of the letter was Greenwood, thus collaborating the existence of the building and the historic use of the name ‘Greenwood.’From the existing information, seems very likely that Greenwood was at least begun in 1839, as planned.”

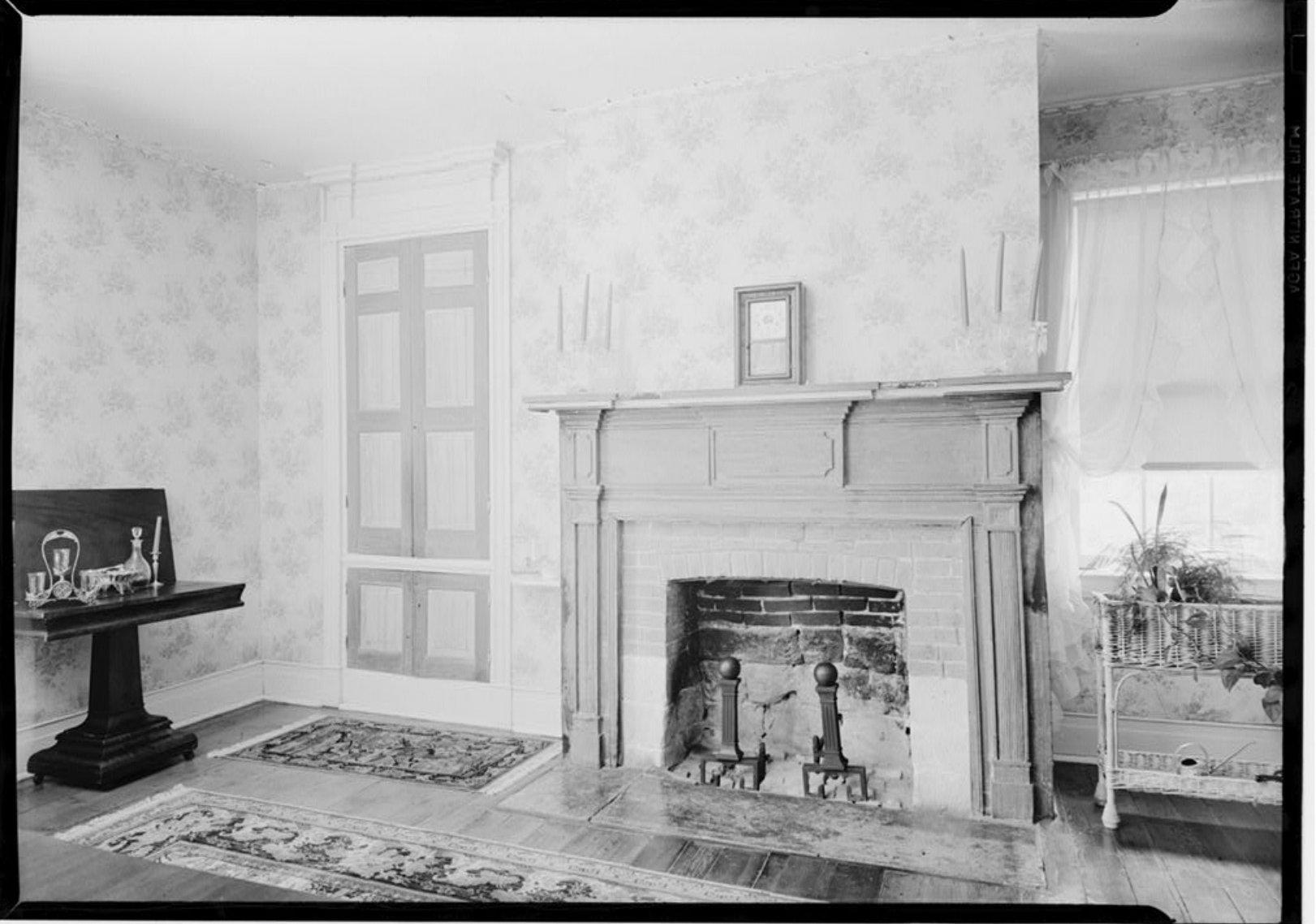

The Historic American Building Survey has preserved seven pictures of Greenwood taken on July 4, 1940, viewable in the gallery below:

Inspired by the preservation of historic homes, our group, CoMo Preservation, hopes to help homeowners, landlords, and institutions prevent the destruction of historic architecture. Original period styles might be replicated, but will forever lack the social history of authentic structures. The preservation of historic buildings is necessary for Columbia’s residents, students, and visitors to achieve a sense of place and, it follows, for our city’s continued economic success. If you want to join us in our mission, signup on our mailing list for news and updates.

Sources

Historic American Building Survey (1959). Greenwood, Columbia vicinity, Boone County, MO. Survey number: HABS MO-1151. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Accessed January 15, 2023.

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Greenwood (1978). Columbia, Missouri: United State Department of the Interior. Accessed on January 15, 2023.

Moser, Kate (July 21, 2008). If These Walls Could Talk. Columbia, Missouri: Columbia Missourian. Accessed on January 15, 2023.

Wikipedia contributors. (2023, January 6). Federal architecture. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15:21, January 15, 2023.

Do you have ideas for future topics? Interested in writing an entry or sharing a photo? Notice an error?

Email CoMoPreservation@gmail.com or leave a comment below.